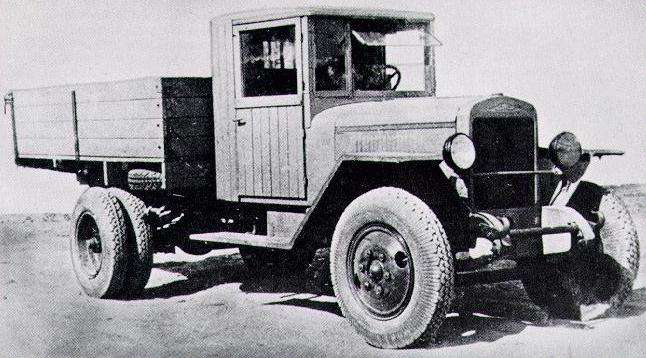

ZIS-5 - The USSR's standard 3 tonne lorry - a licensed version of the Autocar Dispatch SA

The place of the motor vehicle in society 1938

Motor vehicles are one of the technologies used as a measure of modernity during the 20th century and has been contrasted with the older technologies of steam railways and horse-drawn wagons. Yet the Soviet Union with its state control of production and suppression of consumerism, is singularly ill suited to use motorisation a measure of progress. In many ways, it represents an alternative direction of progress and can be used to shed some light on other countries such as Germany during the 1930s and 40s before motor vehicles became widespread.

The first viable motor vehicles appeared in the 1890s, however they did not replace the horse in the transport/draught role until around 1960 in America and even later in European countries and although they eventually replaced the railways in some roles, railways to this day, remain the carrier of choice for bulk raw materials. As David Edgerton [2007] has pointed out, the mechanisation of American farming was achieved using horse power and it depended on 10 million horses for motive power as late as 1939, with the halfway point between a zenith of farm horse use in 1918 with 27 million horses and 1960 when there were just 3 million occurred as late as 1944. The reasons behind this slow change are the high costs of motor vehicles and the extensive infrastructure needed to supply, fuel & lubricants, tyres, spares and engineering support over some distance. Their pattern of introduction reflects these factors and so the first motors appeared in cities with their good communications to supply the necessary supplies and skilled people. The high cost dictated high intensity use like public service vehicles - buses and taxis or haulage roles where speed was at a premium. The horse retained the low cost, low intensity usage, much of the rural usage and the railways only started to suffer competition in the long and middle distance haulage once cheap lorries became available as war surplus after the Great War. [See Thompson] [also Gerhold]

Wartime version of the GAZ-MM with one headlight and wooden cab.

With price being a key determiner of uptake, the GDP per head of population was an important indicator of whether motor vehicles spread outside of these high value roles. America had a GDP per capita of 6,126 [see Maddison 1990 US Dollars] in 1938 and with low prices from Ford's mass production techniques, passenger car use spread rapidly during the 1920s, while Great Britain had a value of 6,266 but with higher costs from smaller manufacturers had a slower uptake. As Adam Tooze has demonstrated, Germany with a value of 4,994 simply did not have workers with a sufficiently high income to buy the Volkswagen, even with government subsidies and a hire-purchase scheme. So in 1938 America had motor vehicles in the cities, personal car ownership was well established and farming was half horse drawn, while most of Europe was well behind this level of development with mainly commercial motor vehicles, limited private ownership and agriculture that was mainly horse-drawn. This was reflected in both the stock of motor vehicles and in their production capacity as seen here:

| World motor vehicle production 1938 | ||||||

| total | Passenger cars | Trucks & lorries | Others | motorcycles | tractors | |

| United States 1937 | 4,732,553 | 3,847,800 | 602,144 | 282,609 | ???? | 283,155 |

| United Kingdom 1937 | 493,000 | 379,310 | 113,946 | 45,000 | 10,679 | |

| Germany 1938 | 376,769 | 289,108 | 87,661 | 199,299 | ||

| USSR 1938 | 211,100 | 27,000 | 182,400 | 1,700 | 51,000 | 120,000 ~ |

| ~ figure for 1937 as more indicative since production for 1938 was 55,000 due a change of model | ||||||

| Stock of motor vehicles 1939 | ||||||

| Horses | Motor vehicles | Passenger cars | Trucks & lorries | Tractors | Per 1000 people | |

| United States | 10,815,000 | 30,615,000 | 26,201,000 | 4,414,000 | 1,567,430 | 233 |

| United Kingdom | 987,000 | 3,157,000 | 2,132,000 | 492,000 | 52,000 | 66 |

| Germany | 3,000,000 | 1,986,122 | 1,535,431 | 450,641 | 25 | |

| USSR | 20,200,000 | 890,000 | 125,000 | 766,880 | 438,000 | 5 |

The differences are plain to see, the United States possessed up to 80% of the world production capacity for motor vehicles leaving the British Empire and other European countries such as Germany, France, Italy, Spain the remaining 20%. This growth had gone on for most of the interwar period so the United States had built up an impressive stock of vehicles far in excess of any other country, even in relation to their population size. Motor vehicles occupied the public transport role in cities and in the country, a thriving cargo haulage sector and extensive use in agriculture but most importantly, widespread private ownership of passenger cars. Europe by contrast had motor public transport in cities, a small cargo haulage sector with strong rail transport, horse-drawn agriculture and passenger cars restricted to business or the wealthy. Horse use was widespread in the rural economy across Europe and mechanisation took other forms such as electric milking parlours in Germany.

The current status of motor vehicles in society was reflected in their military use. Armies across Europe remained close to their Great War predecessors, being composed largely of infantry units which were transported by railways, had horse-drawn artillery and unit transport and used motor vehicles to connect these with the railhead. Tanks were usually deployed in the infantry support role or in a limited number of new, specialised, armoured divisions which were fully motorised. Given the limited means in terms of production and stock of motor vehicles, European armies were hard pressed even to maintain these levels of motorisation. For instance, in early 1940 the German Army considered de-motorising, as losses from the the Polish Campaign and wear and tear exceeded their monthly allocation of vehicles. [See Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg. Band 5 Bernhard R Kroener] The successful conclusion of the French Campaign resulted in a one off tranche of vehicles which allowed the expansion of the German Army before the attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. However the expansion from the original 6 to 10 and later 21 Panzer Divisions by June 1941 was only achieved by stripping the Infanterie Divisions of much of their motor transport. In September 1939 an Infanterie Division (1.Welle) originally had 8: 30-tonne Motor Columns 1: 25-cbm Fuel Column and 3: 36-tonne Artillery Columns. By May 1940, the Artillery Columns had gone and the transport consisted of 3: 30-tonne Motor Columns 1: 25-cbm Fuel Column and 3: 30-tonne Horse Columns. For the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the same 1.Welle Divisions had the same transport but with the addition of 3: 15-tonne Light (Horse) Columns, however of the 100 Infanterie Divisions only 56 were fully equipped with German equipment, 17 had French equipment and 27 had a reduced scale of motor vehicles. When facing its longest and most sustained marches in Russia, the Infanterie Divisions relied on horse-drawn transport to the largest degree since the Great War.

Destroyed Soviet trucks in the Winter War 1940

The search for Soviet statistics

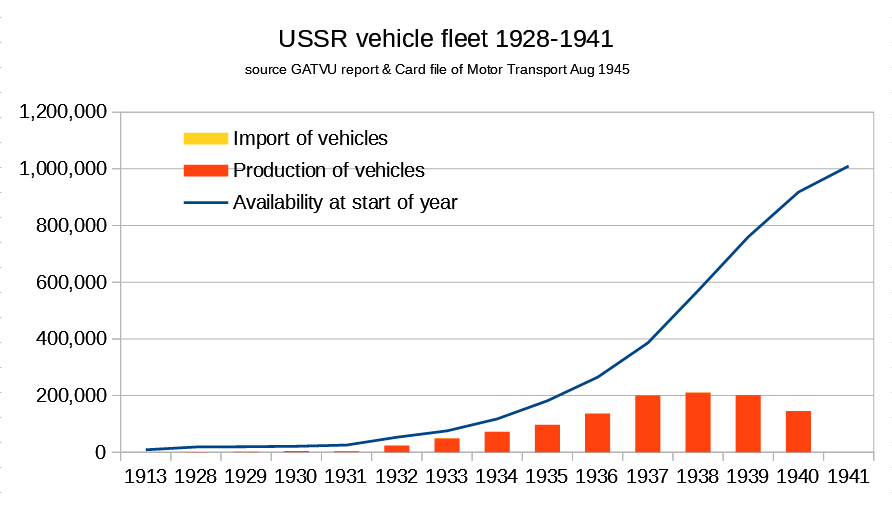

Holland Hunter in his book "Soviet Transport Experience" elegantly describes the problem facing the Soviet researcher, in that there are motor vehicle production statistics for every year available in handbooks but no stock figures. There was a census of all the vehicles in the Soviet Union carried out in 1928 at the start of the First Five Year Plan but nothing after that until 1940 except for partial figures on tractors on farms and agricultural lorries. Hunter's solution to this is to use the production series from 1928 to 1941, add and subtract the few imports and exports and to use a scrappage figure taken from US usage and fitted to meet the few figures that are to hand. This methodology works well for the period up to 1939 but at this point, the territorial acquisitions of the USSR and the extra machines obtained from them, coupled with the losses in fighting in Poland and Finland, create difficulties. In addition there is the very high rate of un-serviceable vehicles, up to 45%, found in the civilian economy in June 1941. It could be that the large number of Soviet enterprises which held small numbers of vehicles, did not report when they wore out or were written off in accidents but simply pushed them into a shed and draped a tarpaulin over the wreckage and kept it 'on the books'. Unfortunately Hunter in this book confines his researches to only lorries and only in the later "Soviet Transport Sector" 1969 he does give some figures for passenger cars. However Orlov does provide some further figures for 1928 which can be used to fill in the gaps.

However since 1991 there has been a steady release of old Soviet Statistical Handbooks which fill out the picture for the stock figures. From these partial breakdown of the stock of vehicles for the period 1932 to 1945 can be built up including figures for tractors and motorcycles.

The range of figures available for the stock of motor vehicles in 1940, varies from 1,148,929 vehicles which is a simple addition of the production figures from 1924 to 1940, 1,092,000 vehicles (272,000 military, 820,000 civil with 370,000 un-serviceable) as given in the Military Thought article "Transportation in the Great Patriotic War" and in the GATVU report written at the end of the war. The official German history gives a figure of 1,002,600 for 1939 based on Harrison and the lowest figure is 807,000 vehicles as given in the "Soviet Economy in the Great Patriotic War" and in "Russia at War" by Alexander Werth.

The picture that emerges is a very different one from the classic development of motor vehicles seen in Western countries. From a very low base in 1928 of around 16,400 motor vehicles (7,500 passenger cars, 6,500 cargo lorries, 1,100 buses and 1,300 special vehicles) [Statistical handbook of USSR 1928] made up of imported and license built vehicles many of which were unservicable, the Soviet government came to an agreement in May 1929 with the Ford Motor Company to build a state of the art factory to mass production vehicles and grow the Soviet fleet. The factory was a copy of the Ford River Rouge factory complex completed in 1928 and designed by Albert Kahn which literally turned raw materials into finished vehicles starting with the Ford Model A in 1927.

Using the American plans and technical assitance, the Gorky Motor Plant (Gorkovsky Avtomobilny Zavod Го́рьковский автомоби́льный заво́д) or GAZ (ГАЗ) started production in Jan 1932 building a license version of the Ford A truck – GAZ-AA while in Moscow the AMO factory was re-equipped by the A.J. Brandt Co. and started building the ZIS-5. In effect the Soviet government had gone out and bought the very latest mass production techniques and equipment and was intending a huge leap forward in the numbers of vehicles in the USSR.

The production from these new factories grew to a peak in 1938 of 211,000 vehicles a year, however in direct contrast to European countries the bulk of this production was in lorries not passenger cars and in this category the USSR exceeded the output of both Great Britain and Germany. The fall of in production after 1938 was due to increasing problems of transport within the USSR as the railways struggled to cope with the demands of the economy and the diversion of raw materials such as steel for other manufacturing uses. The growth in stock of motor vehicles rose steeply until 1940 when it began to plateau due to the slowing of production, coupled with the start of retirement of the first production batches from 1932.

The Soviet Union of June 1941 was a contradiction in many ways with a large GDP 405,220 but a large population of 188,498,000 inhabitants, giving a GDP per head of population in 1938 of 2,144 (1990 Int. GK$) [figures from Madisson] which was very low compared to most European countries such as Italy 3,316, Germany 4,994 and UK with 6,266. The economy had a large heavy industrial sector and small groups of individually talented designers who could produce innovative designs of tanks such as the T-34 and KV-1 or aircraft such as the MIG-1, LaGG-1, Pe-2 and Il-2. In agriculture the Soviet Union was a leader in mechanisation, with a tractor usage second only to the United States and in advance of most European countries which still relied on horse-drawn agriculture.

Yet this was a thin veneer of modernity concealing an overall low level of development, probably roughly on a par with Italy albeit several times larger. The economy lacked light industry able to produce electronics, optics and advanced technologies such as pharmaceuticals. Although Soviet industry was able to produce high quality artillery pieces and innovative ones such as the Katyushka BM-13 rockets, more complex projects such as the РПР-82 bazooka failed to appear in 1940 and only entered service in 1950, leaving the RPG-43 hand thrown grenade as the main infantry anti-tank weapon. Many innovations relied on foreign technology, the T-34 tank used the American Christie suspension, most aircraft relied on aero engines that were improved versions of French Gnome and Hispano-Suiza ones, the Li-2 transport aircraft was a license built copy of a US design and Soviet motor vehicles were licensed copies of American models. Many large Soviet factories were copies of Western ones equipped with machine tools bought from America and Germany. While the farms had tractors, the efficiency and productivity of the Collective Farms and State Farms was extremely low and the Motor Tractor Stations were expensive to run.

Part two

In the next part, I hope to examine the balance of vehicles during the Russo-German war.